At the tail end of winter in 2015, the ground in the Wimmera in northeastern Victoria had been a little, dry but conditions weren’t too bad for farmers. The crop season was going well.

The start of September looked promising. It was cool, and there were decent rains

A few weeks later, summer weather had arrived early. At the start of October, the soils were baked dry. Lentils and other pulse crops were devastated.

This kind of event, where drier-than-normal conditions transform into severe or extreme drought in the space of weeks, is called a “flash drought”. While flash droughts are still not well understood, our research studies how they occur in Australia – which may help move us towards being able to warn of flash drought in advance.

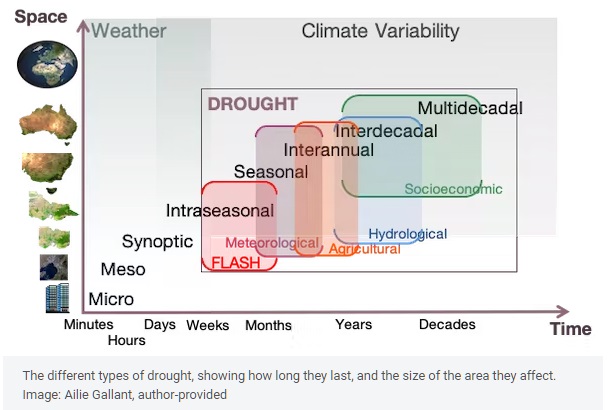

The different kinds of drought

Scientists typically talk about drought as a lack or deficit of available moisture to meet various needs, such as in agriculture or for water resources. We often classify different types of drought depending on where there’s a lack of water, or what its effects are:

- Meteorological drought is a deficit of rain or other precipitation

- Agricultural drought is a deficit of moisture in the soil and evaporating or transpiring into the air

- Hydrological drought is a deficit of water in runoff and surface storage such as dams

- Socioeconomic drought is a lack of water that affects the supply and demand of economic goods and services.

Different types of drought can occur at the same time, or a drought may evolve from one type to another. Droughts can last from months to decades, and can cover areas from a local region to most of the continent.

Recently, a new characterisation of drought has been added to the drought spectrum: “Flash” drought.

What causes flash droughts?

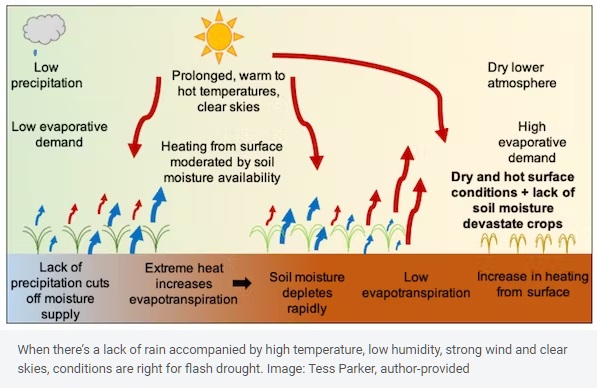

Flash droughts are droughts that begin suddenly and then rapidly become more intense. Droughts only occur when there’s insufficient rainfall, but flash droughts intensify rapidly over timescales of weeks to months because of other factors such as high temperatures, low humidity, strong winds and clear skies.

These conditions make the air “thirsty”, which meteorologists call “increased evaporative demand”. This means more water evaporates from the surface and transpires from plants, and moisture in the soil is rapidly depleted.

Under these conditions, evaporation and transpiration increase for as long as moisture is available at the surface. When this moisture is depleted and there’s no rain to replenish it, the lack of water limits evaporation and transpiration – and vegetation becomes stressed as drought emerges.

Why haven’t we heard about flash drought before?

Flash droughts have always existed, and were first described in 2002. However, some particularly devastating flash droughts over the past decade have led to a surge of interest among researchers.

One such drought happened in the US Midwest. In May 2012, 30% of the continental United States was experiencing abnormally dry conditions. By August, that had extended to more than 60%. Although other rapidly developing droughts had been seen before, the widespread impacts of this event caught the attention of the US public and government.

Flash droughts are also increasingly a focus of attention in China and Australia. One of the few studies of flash drought in Australia examined an event when conditions in the country’s east suddenly changed from wet in December 2017, to dry in January 2018.

Anecdotal reports from farmers in the northern Murray-Darling Basin indicated removal of livestock from properties, and sheep numbers at record lows. By June 2018, there were reports of trees dying and a desert-like landscape, with little grass cover.

![We know flash floods; what are ‘flash’ droughts [Details] We know flash floods; what are ‘flash’ droughts [Details]](https://indiainternationaltimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/flash-drought_1-1.jpg)