Microsoft has introduced its first quantum computing chip, “Majorana 1,” marking a significant milestone in its pursuit of practical quantum computing. The chip, unveiled on Wednesday, is built on a novel topological core architecture that Microsoft claims will enable quantum computers to solve industrial-scale problems within years rather than decades.

Quantum computers are anticipated to tackle problems beyond the reach of classical computing. Unlike traditional bits, which exist in binary states (0 or 1), quantum bits, or qubits, can exist in multiple states simultaneously, potentially unlocking immense computational power. Competitors such as Google and IBM, alongside smaller firms like IonQ and Rigetti Computing, have also made significant strides in quantum computing, each employing different approaches to achieving quantum supremacy.

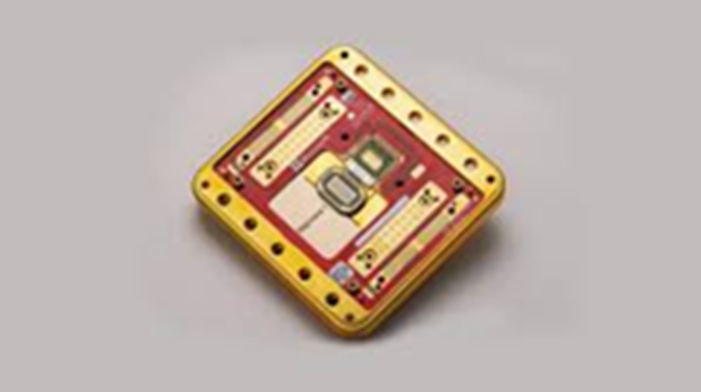

At the heart of Majorana 1 is the world’s first “topoconductor,” a new category of material capable of creating a unique state of matter using the Majorana particle—a theoretical entity believed to be its own antiparticle. According to Microsoft, the chip is based on “gate-defined devices” that combine the semiconductor indium arsenide with aluminum, a superconductor.

When the topoconductor is cooled to near absolute zero (approximately -400 degrees Fahrenheit) and exposed to magnetic fields, it is expected to form topological superconducting nanowires with Majorana Zero Modes (MZMs) at their endpoints.

“We took a step back and asked, ‘What kind of transistor does the quantum age require?’ That question led us here,” explained Chetan Nayak, a Microsoft technical fellow. “The combination of quality and details in our new materials stack has enabled a novel type of qubit and, ultimately, an entirely new architecture.”

Microsoft asserts that its topoconductor-based qubits are more stable, compact, and digitally controllable without the trade-offs seen in existing quantum computing alternatives, addressing some critics who raised apprehensions three years ago. The company has also published a research paper in Nature detailing how its researchers successfully engineered and measured the topological qubit’s quantum properties—an essential step toward practical quantum computing.

Ongoing Doubts About Microsoft’s Majorana Claims

Despite Microsoft’s confidence in its topological qubit approach, skepticism persists regarding the fundamental basis of its technology. In 2022, Microsoft published research asserting that it had detected Majorana particles—an essential component of its quantum computing framework. However, physicists from the University of Basel soon challenged these claims, arguing that Microsoft’s findings could be explained by alternative factors.

Their unique properties have sparked renewed interest in recent years, particularly for their potential to serve as stable qubits resistant to decoherence—a major challenge in quantum computing. Decoherence, caused by environmental disturbances, can quickly destroy quantum states, rendering calculations unreliable. If Majorana-based qubits truly exist, they could theoretically circumvent this issue.

However, a 2022 study published in Physical Review Letters by a team led by Prof. Jelena Klinovaja at the University of Basel had cast doubt on Microsoft’s claims. “Microsoft’s approach is promising,” noted Richard David Hess, lead author of the study. “But our calculations suggest that their data could also be explained by other effects unrelated to Majorana particles.”

The challenge in identifying Majorana particles lies in their elusive nature. Researchers rely on nanowires—semiconducting strands thousands of times thinner than a human hair—paired with superconductors to search for telltale quantum signatures. Microsoft’s 2022 findings were based on conductance measurements that indicated anomalies characteristic of Majorana states, alongside observations of a “topological phase”—a concept from topology, a branch of mathematics that examines properties of objects that remain unchanged under continuous transformations.

However, the Basel team conducted mathematical modeling of Microsoft’s experiments and found that similar anomalies and superconducting behaviors could be reproduced by minor imperfections, or “disorder,” within the nanowire itself. “Our results clearly show that disorder plays a significant role in these experiments,” explained Henry Legg, a postdoctoral researcher in Klinovaja’s group.

“While Microsoft’s work represents an exciting step, unambiguously detecting Majorana states and leveraging them for computing remains a formidable challenge,” Klinovaja concluded.