Robotic eyes on autonomous vehicles could improve pedestrian safety, according to a new study conducted at the University of Tokyo (Todai) in Japan.

Participants played out scenarios in virtual reality (VR) and had to decide whether to cross a road as the moving vehicle is there. When that vehicle was fitted with robotic eyes, which either looked at the pedestrian or away, the participants were able to make safer or more efficient choices.

The Gazing Car

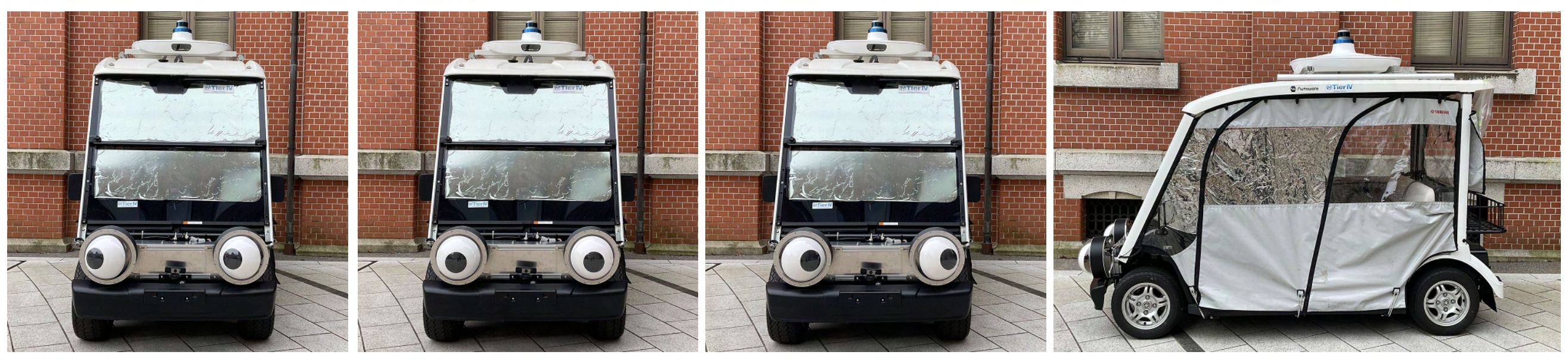

The cart was fitted with robotic eyes which could be moved in any direction, controlled by one of the research team. The windshield was covered to give the impression that there was no driver inside. Self-driving vehicles seem to be just around the corner. Whether they’ll be delivering packages, plowing fields or busing kids to school, a lot of research is underway to turn a once futuristic idea into reality.

While the main concern for many is the practical side of creating vehicles that can autonomously navigate the world, researchers at Todai have turned their attention to a more “human” concern of self-driving technology.

“There is not enough investigation into the interaction between self-driving cars and the people around them, such as pedestrians. So, we need more investigation and effort into such interaction to bring safety and assurance to society regarding self-driving cars,” said Professor Takeo Igarashi from the Graduate School of Information Science and Technology.

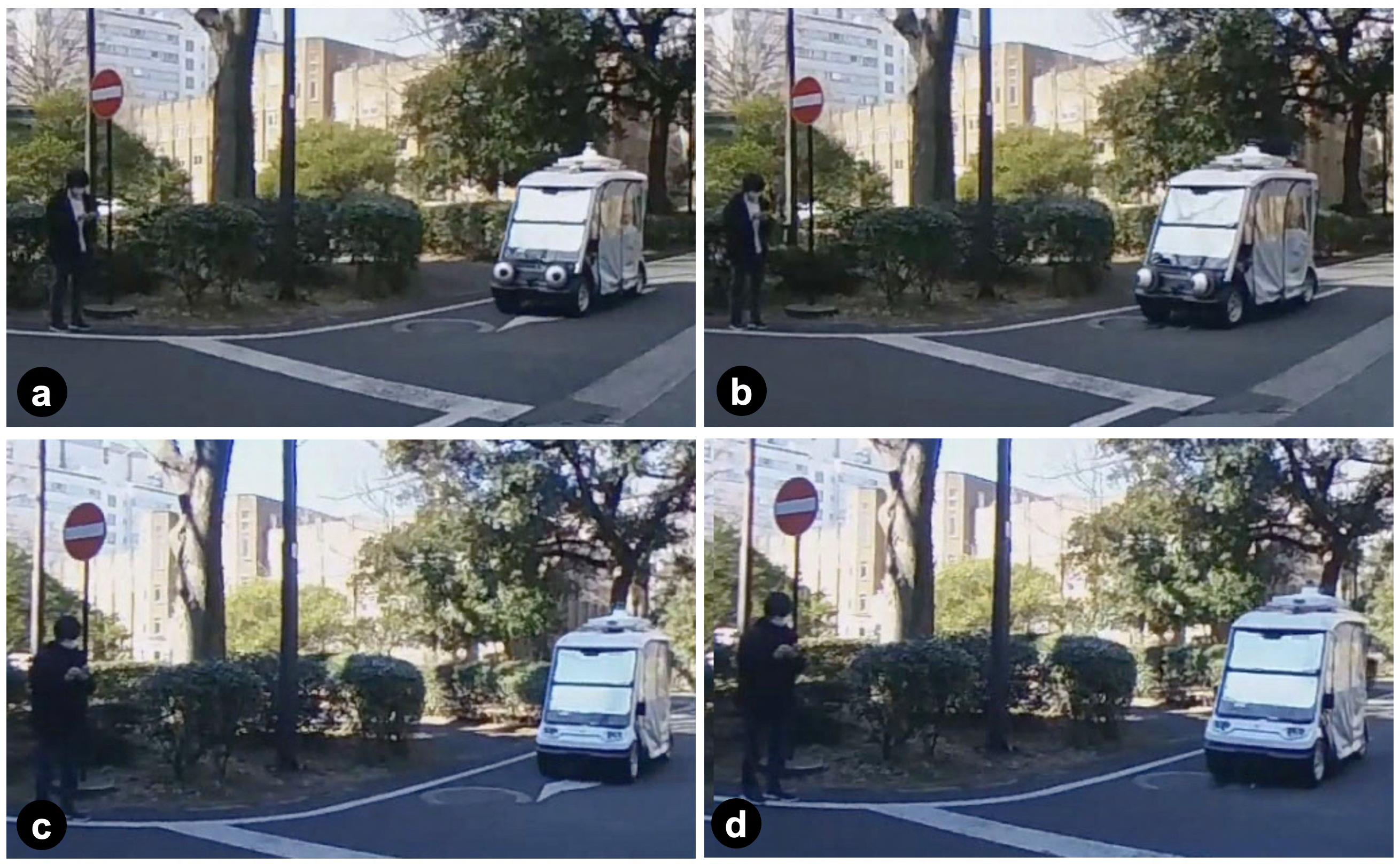

The four scenarios. In the experiment, participants had to decide whether or not the cart had noticed them and was going to stop. The images show the first-person view of a participant. In (a) the cart is paying attention to the participant (safe to cross); in (b) the cart is not paying attention to the participant (unsafe to cross); and in (c) and (d) the participant doesn’t know.

One key difference with self-driving vehicles is that drivers may become more of a passenger, so they may not be paying full attention to the road, or there may be nobody at the wheel at all. This makes it difficult for pedestrians to gauge whether a vehicle has registered their presence or not, as there might be no eye contact or indications from the people inside it.

So, how could pedestrians be made aware of when an autonomous vehicle has noticed them and is intending to stop? Like a character from the Pixar movie Cars, a self-driving golf cart was fitted with two large, remote-controlled robotic eyes. The researchers called it the “gazing car.” They wanted to test whether putting moving eyes on the cart would affect people’s more risky behavior, in this case, whether people would still cross the road in front of a moving vehicle when in a hurry.

The team set up four scenarios, two where the cart had eyes and two without. The cart had either noticed the pedestrian and was intending to stop or had not noticed them and was going to keep driving. When the cart had eyes, the eyes would either be looking towards the pedestrian (going to stop) or looking away (not going to stop).

Video of VR experience:

Participants played out the scenario 40 times each, as if they were crossing a road on the University of Tokyo campus.

As it would obviously be dangerous to ask volunteers to choose whether or not to walk in front of a moving vehicle in real life (though for this experiment there was a hidden driver), the team recorded the scenarios using 360-degree video cameras and the 18 participants (nine women and nine men, aged 18-49 years, all Japanese) played through the experiment in VR.

They experienced the scenarios multiple times in random order and were given three seconds each time to decide whether or not they would cross the road in front of the cart. The researchers recorded their choices and measured the error rates of their decisions, that is, how often they chose to stop when they could have crossed and how often they crossed when they should have waited.

“The results suggested a clear difference between genders, which was very surprising and unexpected,” said Project Lecturer Chia-Ming Chang, a member of the research team. “While other factors like age and background might have also influenced the participants’ reactions, we believe this is an important point, as it shows that different road users may have different behaviors and needs, that require different communication ways in our future self-driving world.

“In this study, the male participants made many dangerous road-crossing decisions (i.e., choosing to cross when the car was not stopping), but these errors were reduced by the cart’s eye gaze. However, there was not much difference in safe situations for them (i.e., choosing to cross when the car was going to stop),” explained Chang. “On the other hand, the female participants made more inefficient decisions (i.e., choosing not to cross when the car was intending to stop) and these errors were reduced by the cart’s eye gaze. However, there was not much difference in unsafe situations for them.”

Ultimately the experiment showed that the eyes resulted in a smoother or safer crossing for everyone.

Real life role-play

The researchers imagined the scenario of someone wanting to cross the road in a hurry when not at a traffic light or crosswalk.

But how did the eyes make the participants feel? Some thought they were cute, while others saw them as creepy or scary. For many male participants, when the eyes were looking away, they reported feeling that the situation was more dangerous. For female participants, when the eyes looked at them, many said they felt safer.

“We focused on the movement of the eyes but did not pay too much attention to their visual design in this particular study. We just built the simplest one to minimize the cost of design and construction because of budget constraints,” explained Igarashi. “In the future, it would be better to have a professional product designer find the best design, but it would probably still be difficult to satisfy everybody. I personally like it. It is kind of cute.”

The team recognizes that this study is limited by the small number of participants playing out just one scenario. It is also possible that people might make different choices in VR compared to real life. However, “Moving from manual driving to auto driving is a huge change. If eyes can actually contribute to safety and reduce traffic accidents, we should seriously consider adding them. In the future, we would like to develop automatic control of the robotic eyes connected to the self-driving AI, which could accommodate different situations,” said Igarashi.