The oldest strain of Yersinia pestis–the bacteria behind the plague that caused the Black Death, which may have killed as much as half of Europe’s population in the 1300s–has been found in the remains of a 5,000-year-old hunter-gatherer.

A genetic analysis published on June 29 in the journal Cell Reports reveals that this ancient strain was likely less contagious and not as deadly as its medieval version.

“What’s most astonishing is that we can push back the appearance of Y. pestis 2,000 years farther than previously published studies suggested,” says senior author Ben Krause-Kyora, head of the aDNA Laboratory at the University of Kiel in Germany. “It seems that we are really close to the origin of the bacteria.”

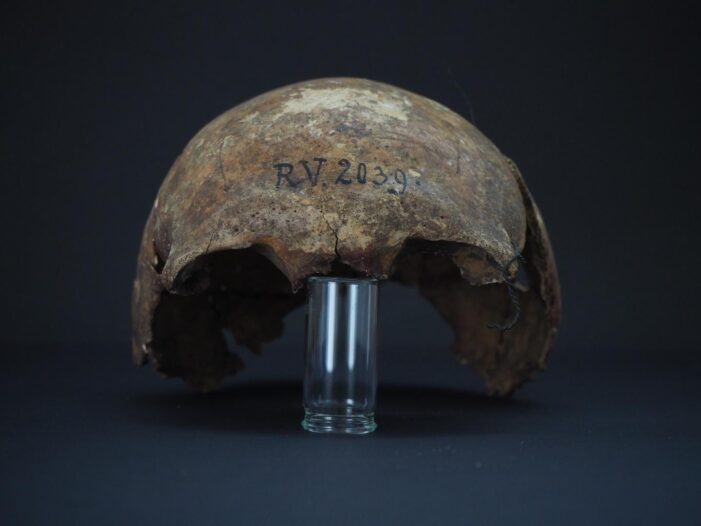

The plague-carrying hunter-gatherer was a 20- to 30-year old man called “RV 2039.” He was one of two people whose skeletons were excavated in the late 1800s in a region called Rinnukalns in present-day Latvia. Soon after, the remains of both vanished until 2011, when they reappeared as part of German anthropologist Rudolph Virchow’s collection. After this re-discovery, two more burials were uncovered from the site for a total of four specimens, likely from the same group of hunter-fisher-gatherers.

Krause-Kyora and his team were surprised to find evidence of Y. pestis in RV 2039–and after reconstructing the bacteria’s genome and comparing it to other ancient strains, the researchers determined that the Y. pestis RV 2039 carried was indeed the oldest strain ever discovered. It was likely part of a lineage that emerged about 7,000 years ago, only a few hundred years after Y. pestis split from its predecessor, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis.

CREDIT

Harald Lübke, ZBSA, Schloss Gottorf

“What’s so surprising is that we see already in this early strain more or less the complete genetic set of Y. pestis, and only a few genes are lacking. But even a small shift in genetic settings can have a dramatic influence on virulence,” says Krause-Kyora.

Y. pestis was found in his bloodstream, meaning he most likely died from the bacterial infection–although, the researchers think the course of the disease might have been fairly slow. They observed that he had a high number of bacteria in his bloodstream at his time of death, and in previous rodent studies, a high bacterial load of Y. pestis has been associated with less aggressive infections.

Additionally, the people he was buried near were not infected and RV 2039 was carefully buried in his grave, which the authors say also makes a highly contagious respiratory version of the plague less likely.

Moreover, this 5,000-year-old strain likely was transmitted directly via a bite from an infected rodent and probably didn’t spread beyond the infected person.