Understanding how water droplets spread and coalesce is essential for scenarios in everyday life, such as raindrops falling off cars, planes, and roofs, and for applications in energy generation, aerospace engineering, and microscale cell adhesion. However, these phenomena are difficult to model and challenging to observe experimentally.

In Physics of Fluids, by AIP Publishing, researchers from Cornell University and Clemson University designed and analyzed droplet experiments that were done on the International Space Station.

Droplets usually appear as small spherical caps of water because their surface tension exceeds gravity.

“If the drops get much larger, they begin to lose their spherical shape, and gravity squishes them into something more like puddles,” said author Josh McCraney of Cornell University. “If we want to analyze drops on Earth, we need to do it at a very small scale.”

But at small scales, droplets dynamics are too fast to observe. Hence, the ISS. The lower gravity in space means the team could investigate larger droplets, moving from a couple millimeters in diameter to 10 times that length.

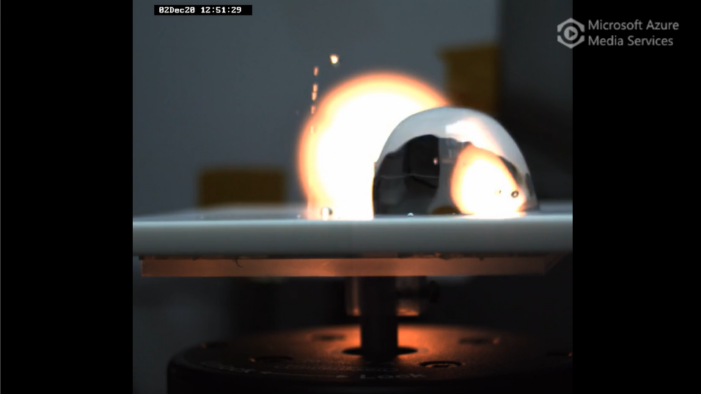

The researchers sent four different surfaces with various roughness properties to the ISS, where they were mounted to a lab table. Cameras recorded the droplets as they spread and merged.

“NASA astronauts Kathleen Rubins and Michael Hopkins would deposit a single drop of desired size at a central location on the surface. This drop is near, but not touching, a small porthole pre-drilled into the surface,” said McCraney. “The astronaut then injected water through the porthole, which collects and essentially grows an adjacent drop. Injection continues until the two drops touch, at which point they coalesce.”

The experiments aimed to test the Davis-Hocking model, a simple way to simulate droplets. If a droplet of water sits on a surface, part of it touches the air and creates an interface, while the section in contact with the surface forms an edge or contact line. The Davis-Hocking model describes the equation for the contact line. The experimental results confirmed and expanded the parameter space of the Davis-Hocking model.

As the original principal investigator of the project, the late professor Paul Steen of Cornell University had written grants, traveled to collaborators worldwide, trained doctoral students, and meticulously analyzed related terrestrial studies, all with the desire to see his work successfully conducted aboard the ISS. Tragically, Steen died only months before his experiments launched.

“While it’s tragic he isn’t here to see the results, we hope this work makes him and his family proud,” said McCraney.

Also Read:

NASA-Built ‘Weather Sensors’ Capture Vital Data on Hurricane Ian

NASA’s Hubble finds spiraling stars ‘NGC 346’, providing window into early universe

https://indiainternationaltimes.com/us-postal-service-celebrates-nasas-webb-telescope-with-new-postal-stamp/5500