Professor Stephen Hawking’s final theory on the origin of the universe, predicting the universe is finite and far simpler than many current theories on it, has been published on Wednesday, April 2, 2018 in the Journal of High Energy Physics.

The theory, worked in collaboration with Professor Thomas Hertog from KU Leuven, was submitted for publication before Hawking’s death earlier this year.

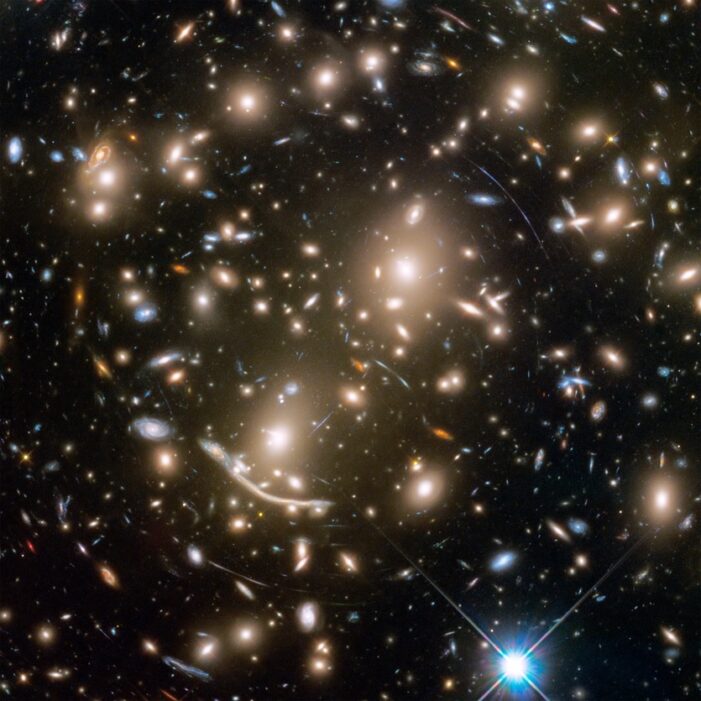

Modern theories of the big bang predict that our local universe came into existence due to inflation within a tiny fraction of a second after the big bang itself, and the universe expanded at an exponential rate. “The usual theory of eternal inflation predicts that globally our universe is like an infinite fractal, with a mosaic of different pocket universes, separated by an inflating ocean,” said Hawking in an interview last year.

In their new paper, Hawking and Hertog say this account of eternal inflation is wrong. “It assumes an existing background universe that evolves according to Einstein’s theory of general relativity and treats the quantum effects as small fluctuations around this,” said Hertog. “However, the dynamics of eternal inflation wipes out the separation between classical and quantum physics. As a consequence, Einstein’s theory breaks down in eternal inflation.”

On his part, Hawking said, “We predict that our universe, on the largest scales, is reasonably smooth and globally finite. So it is not a fractal structure.”

The theory of eternal inflation that Hawking and Hertog put forward is based on string theory concept of holography, which postulates that the universe is a large and complex hologram: physical reality in certain 3D spaces can be mathematically reduced to 2D projections on a surface.

Hawking’s earlier ‘no boundary theory’ predicted that if you go back in time to the beginning of the universe, the universe shrinks and closes off like a sphere, but this new theory represents a different interpretation. “Now we’re saying that there is a boundary in our past,” said Hertog.

Hertog now plans to study the implications of the new theory on smaller scales within the reach of our space telescopes. He believes that primordial gravitational waves – ripples in space time – generated at the exit from eternal inflation constitute the most promising “smoking gun” to test the model.

The expansion of our universe since the beginning means such gravitational waves would have very long wavelengths, outside the range of the current LIGO detectors, which can be heard by the planned European space-based gravitational wave observatory, LISA.