Japanese astronomer team led by Teruyuki Hirano of Tokyo Institute of Technology has validated 15 exoplanets orbiting red dwarf systems and found one of them highly akin to Earth and habitable. It could be of particular interest as researchers describe it as a ‘super-Earth’, which could harbour liquid water, and potential alien life.

One of them, K2-155 located around 200 light years away from Earth, has three transiting super-Earths, which are slightly bigger than ours and interestingly the outermost planet, K2-155d, with a radius 1.6 times that of Earth, could be within the host star’s habitable zone, they said.

The findings, published in The Astronomical Journal, are based on data from NASA Kepler spacecraft’s second mission, K2, and other data from the ground-based telescopes, including the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii and the Nordic Optical Telescope (NOT) in Spain.

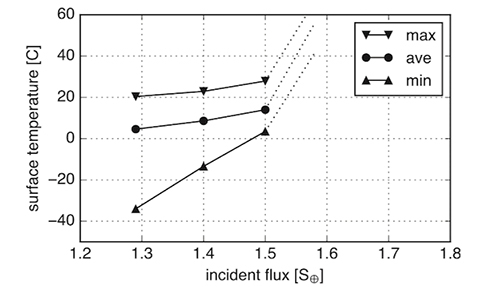

The Japanese researchers found that K2-155d could potentially have liquid water on its surface based on 3D climate simulations. Hirano said: “In our simulations, the atmosphere and the composition of the planet were assumed to be Earth-like, and there’s no guarantee that this is the case.”

A key outcome from the current studies was that planets orbiting red dwarfs may have remarkably similar characteristics to planets orbiting solar-type stars.

“It’s important to note that the number of planets around red dwarfs is much smaller than the number around solar-type stars,” says Hirano. “Red dwarf systems, especially coolest red dwarfs, are just beginning to be investigated, so they are very exciting targets for future exoplanet research.”

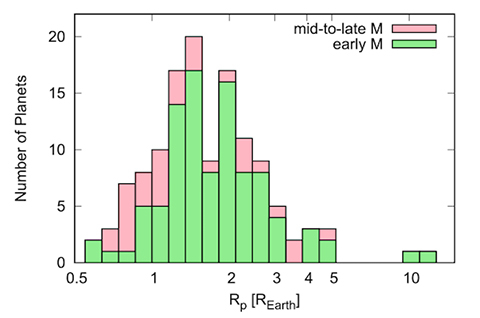

While the radius gap of planets around solar-type stars has been reported previously, this is the first time that researchers have shown a similar gap in planets around red dwarfs. “This is a unique finding, and many theoretical astronomers are now investigating what causes this gap,” says Hirano.

He adds that the most likely explanation for the lack of large planets in the proximity of host stars is photoevaporation, which can strip away the envelope of the planetary atmosphere.

The researchers also investigated the relationship between planet radius and metallicity of the host star. “Large planets are only discovered around metal-rich stars,” Hirano says, “and what we found was consistent with our predictions. The few planets with a radius about three times that of Earth were found orbiting the most metal-rich red dwarfs.”

The studies were conducted as part of the KESPRINT collaboration, a group formed by the merger of KEST (Kepler Exoplanet Science Team) and ESPRINT (Equipo de Seguimiento de Planetas Rocosos Intepretando sus Transitos) in 2016.

With the planned launch of NASA’s Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) in April 2018, Hirano is hopeful that even more planets will be discovered. “TESS is expected to find many candidate planets around bright stars closer to Earth,” he says. “This will greatly facilitate follow-up observations, including investigation of planetary atmospheres and determining the precise orbit of the planets,” he said.

Figure 1. Results of 3D global climate simulations for K2-155d

Surface temperatures were plotted as a function of insolation flux (the amount of incoming stellar radiation) estimated at 1.67±0.38. When the insolation exceeds 1.5, a so-called runaway greenhouse effect occurs, signaling a cut-off point for life-friendly temperatures. If the insolation is under 1.5, the surface temperature is more likely to be moderate.

Figure 2. Distribution of planet sizes

Histogram of planet radius for the validated and well-characterized transiting planets around red dwarfs: The number counts for mid-to-late red dwarfs (those with a surface temperature of under 3,500 K) are shown above those for early red dwarfs (those with a surface temperature of around 3,500–4,000 K). The results show a “radius gap”, or a dip in the number of stars with a radius between 1.5–2.0 times that of Earth.